The Ruvuma Elephant Project

Current initiative

Published

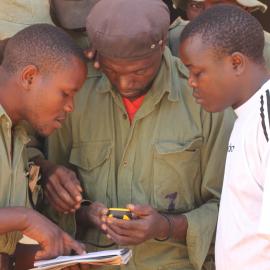

Game guards from the Rumuva Elephant Project. Credit: ©2016 PAMS Foundation

Since 2011, PAMS Foundation has supported over 200 Village Game Scouts and rangers to undertake regular patrols. Together they have arrested many poachers and seized ivory, illegal timber, weapons, snares, poison and other poaching related tools. Thanks to the dedication of these scouts, their community leaders and the assistance of the government, these areas are becoming a safer place for elephants. In addition, PAMS supports local farmers to erect chilli fences, which is a non-aggressive method to dissuade elephants from entering populated and cultivated areas, and is developing alternative income opportunities for local communities.

Location

The Ruvuma Elephant Project covers a 2,500,000 ha area of Tanzania between two protected areas: the Selous Game Reserve, in the south of the country and the Niassa National Reserve, just across the border, in Mozambique. It includes an important wildlife corridor, dominated by miombo woodland, supporting a range of different land uses and rubbing up against an international border; factors which have contributed to it being one of the most notorious areas for elephant poaching in Africa.

The area in question is a mosaic of administrative zones, falling within three local government districts, and including five Wildlife Management Areas (WMA) – managed by community-based organisations that have Authorised Association status to protect and sustainably manage the natural resources. There are also five forest reserves, managed by District Forest Officers; a game reserve managed by the Wildlife Division; and village land managed by local village governments and the Districts.

The poaching and wildlife trade problem

Species affected African Elephant Loxodonta africana

Products in tradeIvory for international markets.

Overview of the problem

The area has extremely high levels of elephant poaching. Poachers are mostly local, with operations financed and organised by outsiders.

The anti-IWT initiative

The Ruvuma Elephant Project was established in 2011, organised by the not for profit organisation PAMS Foundation. Its goals are to establish a reliable picture of elephant status and threat in the area, to understand seasonal movements, control poaching, to ensure law enforcement and prosecution is a real deterrent, and to reduce elephant mortality due to human-elephant conflict.

In essence, community engagement in combating ivory poaching boils down to three types of action on the part of local people: they act as informants, they act as guards, and they change their own behaviour.

The project actively facilitates all three. In return, the people get paid for information, and for carrying out tasks. They get help to protect crops and sell the chilli peppers which are used for crop protection. They are also rewarded for good performance in law enforcement.

The strategy

Strengthening disincentives for illegal behaviour

-

Patrolling has been strengthened through training game scouts and rangers in anti-poaching skills and case reporting. The project has also been implementing joint field patrols where village game scouts accompany wildlife officials and rangers from the District or Wildlife division.

-

Monitoring and data collection has improved through regular air surveillance, carried out over set routes. This provides geographical positioning system (GPS) data for elephant count, carcasses and illegal activity.

-

Establishing incentives and giving rewards to individuals for good performance and information. The resulting intelligence is then fed into special intelligence-led operations.

Their involvement is not without risk. Community guards have been shot and had their homes destroyed by fire. The project, however, is quick to provide compensation and to rebuild morale among those who are committed to wildlife protection. The commitment levels suggest that overall, the rewards outweigh the risks.

Decreasing the costs of living with wildlife

-

Setting up a human-elephant conflict (HEC) mitigation programme – including putting up chili pepper fences and beehive fences to deter elephants from crops.

Increasing livelihoods that are not related to wildlife

-

Supporting income generating activities for WMA communities.

Has the initiative made a difference?

In spite of the recent resurgence in poaching for ivory in Tanzania and Mozambique – and especially in the Niassa area and the Selous ecosystem – results show that the REP has managed to curb elephant poaching in the area. If current anti-poaching activities can be maintained, elephant populations in the REP should remain stable.

In the three and a half years after the project got underway, the impact on poaching was been greater than any other unit or project in Tanzania, with one exception. The Friedkin Conservation Fund (FCF) project, which operates in the north and western parts of the country, and which adopts a very similar approach to REP, has comparable levels of effectiveness.

REP project patrols and aerial surveillance showed a substantial drop in elephant carcasses seen during the first three years of operations (216 were spotted in year one compared to only 68 in year two and less than half of that in year three) – a decline that is not explained by a decline in the elephant population over all. Indeed the population of live elephants has remained stable or marginally increased over the same period. In the last five months of 2014, only one illegally killed elephant carcass was found.

Interventions led to the seizure of 1,582 snares, 25,586 pieces of illegal timber, 175 elephant tusks, 805 firearms, 1,531 rounds of ammunition, 6 vehicles and 15 motorbikes. So far, law enforcement activities have led to the arrest of 562 people

What works and why

The REP explains its success by having a strong focus on working closely with communities to achieve reciprocal support and participation, joint patrols and operations, and intelligence-led activities both in and outside the protected areas.

Those involved in the REP believe that the project works because the area is protected by multiple agencies, rather than a single authority. These include community-based organisations, and a nongovernment organisation which is a specialist in protected area management support (PAMS Foundation) assisting them and the relevant government authorities. Multiple agency involvement increases transparency which hinders corruption.

Another key factor is the high levels of community engagement, which is integrated into and supported by formal law enforcement. This aspect of REP strategy is based on the premise that local involvement in commercial poaching is a manifestation of other problems: the need for case, lack of viable alternatives, lack of understanding of the importance and value of conservation, and lack of good relationships. All these causes need to be recognised and addressed before there can be any long term progress

Factors for success

Supportive, multi-stakeholder partnerships with a shared vision

Sufficient time investment in building relationships and trust between the initiative and local communities

Devolved decision-making power so local communities have a voice in creating or co-creating solutions (as part of the initiative)

What doesn’t work and why

Challenges:

- The proximity of the project area to a long, porous national boundary.

- Working within funding and capacity constraints.

- The sheer scale of the opposition; the poachers’ weaponry and tactics.

- Limited resources and weaponry available for the community scouts.

Lessons learned:

- Don’t raise expectations of communities and then be unable to deliver on those expectations. Promising less and delivering more has proved to be an effective approach to win the support of communities.

- It is important to be sincere, reliable and timely (e.g. with payments) in all dealings.

- Sometimes the path of least resistance is not the path that is right. It is critical not to compromise on principles or do anything that could be legally used against you in the future – even when this might provide a short term fix.

- Don’t limit your friends and allies to a single source – successful projects require support from a wide variety of sources if they are to be sustainable in the long term.

- While financial resources are essential, an integrated strategy, commitment and determination affect success more than just funding.

- Adaptive management is essential. Projects need to be prepared to change course and change tactics if what was originally planned is not working.

Factors that limited or hindered success

Lack of long-term donor support that is flexible, adaptive and/or based on realistic time goals

Organisers, donors and partners

For further information contact People Not Poaching coordinator (peoplenotpoaching@gmail.com).